Critics Reviews

THE BLACKBOARDS by Ruth Weisberg

Ruth Weisberg is an internationally acclaimed artist and the former Dean of Fine Arts at the University of Southern California.

John O’Connor’s blackboard paintings are based on a series of compelling paradoxes. What seems like on accumulation of spontaneous gestures is really the product of painstaking planning and premeditation. Verisimilitude and conceptualism are usually thought of as polar opposites, but in O’Connor’s oeuvre they form a thought-provoking and poetic alliance. In this work, tromp l’oeil realism is placed at the service of such complex ideas as creativity and extinction. The paradox of joining a self-conscious process of cognitive associations with the visual manifestations of the unconscious reflects some of the major currents in twentieth-century art. O’Connor seems to draw on the rationality of late modernism, the free association of Surrealism, and the primacy of questions of representation in Post-Modernism.

Since 1985, the blackboard has been the basis of O’Connor’s work. It re-creates both the autobiographical setting and the quest for knowledge that are the core of O’Connor’s experience. In the artist’s words, “The Blackboard Series has its origins in the classroom where I have been surrounded by blackboards for most of my life–first as a student, then as on artist-teacher. They are the environment of palimpsests, ghosts of gesture, the residue of images and words linking thoughts and concepts of visual entities and written language.”

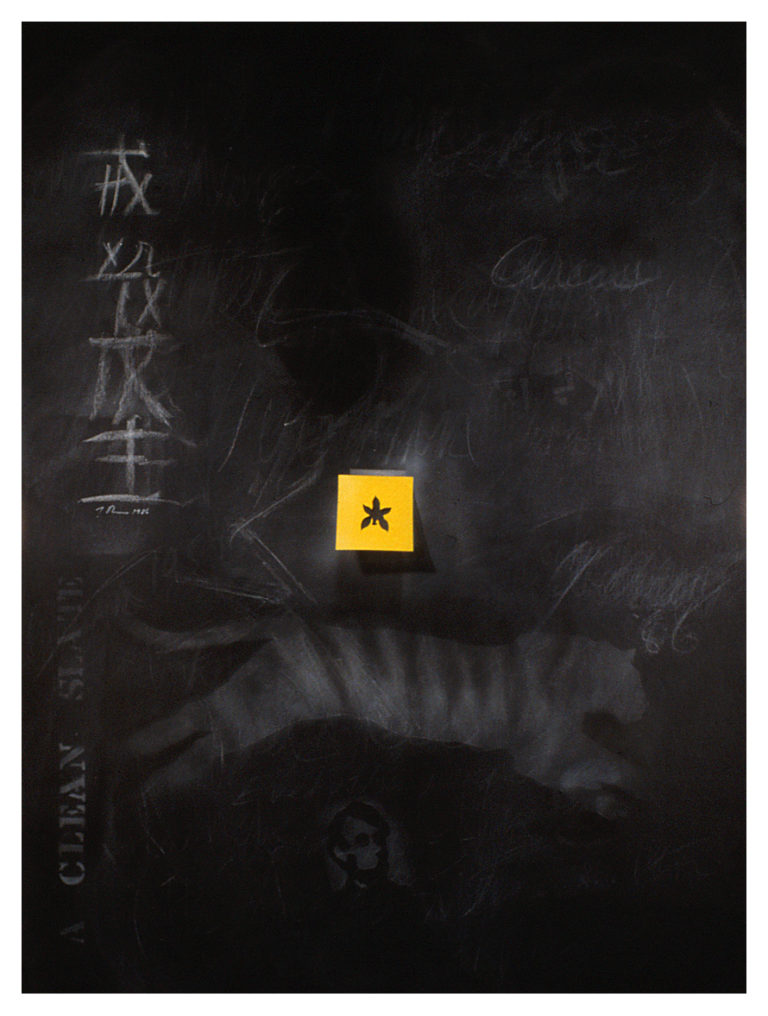

Typically, O’Connor explores concepts that cluster around a central idea. A Clean Slate (1986) is the repository for the artist’s thoughts on the war in Viet Nam. The blackboard evokes both the idea of a “clean slate,” a record showing no discrediting marks, and “to slate,” which is colloquial for severe punishment or harsh criticism. This punning and associative word ploy is overlaid by visual images: a leaping white tiger, oriental calligraphy, the Lincoln and Washington Monuments. The ideas manifested are also reflected in the visual gestalt of the individual paintings. For example, in Works In Progress II (1988)–which is a complex representation of entropy and the relationship of order and chaos–the progression of marks from left to right move from a platonic order to a frenetic mark-making that dissolves any recognition of individual signs into a field of energy.

Many of O’Connor’s paintings feature simple diagrammatical constructions that, in some cases resemble mathematical proofs as in Winter (1992) or Irrational (1994).The sense of palimpsest and dusty overlay has given way to charting and mapping, but the conceptual projections remain very dense.

The open-ended and questioning nature of O’Connor’s work over the last decade is manifested in both its contradictions and in its playfulness. He depicts the inverse reality of the white mark on the dark ground, which can be read as the familiar chalky and didactic blackboard or a constellation of marks defining a deeper mindscape. Whatever readings the viewer brings to these works, John O’Cornor’s poetic and enigmatic paintings have a profound appeal to both the mind and the eye.

BACK TO SCHOOL by Gerard Haggerty

Gerard Haggerty has received support from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Ford Foundation. He writes for ARTnews, and teaches at Brooklyn College, City University of New York.

“As a well-known cabalist once said, ‘If you wish to attain the invisible, you must penetrate the visible to the uttermost.’ ” – Max Beckmann

mixed media

The dust of history is more than a metaphor. We’ve all seen it. In fact, we spent our formative years–day after day–sometimes hungry for knowledge but always eager for recess, staring at that dust. Most folks are likely to think they behold it again when they see the work of John O’Connor, an artist who has spent more than a decade painting representations of blackboards that are virtually indistinguishable from the chalk-dusted slabs of slate they depict.

Three centuries ago, the philosopher John Locke proclaimed that we all enter the world a blank slate, a tabula rasa. O’Connor’s blackboards are anything but blank. Logarithmic spirals, Golden Sections, perspectival diagrams, and other cornerstones of Western visual culture are inscribed on a surface that appears to have been repeatedly rewritten and erased. In more than one sense, there are lessons here: knowledge is ever changing, and history itself can be wiped out. These bittersweet truths are as old as the defaced statues of headless pharaohs, and as modern as the Cultural Revolution that allowed centuries of Chinese art to vanish in the blink of an iconoclast’s eye. As Picasso said of pictures, a culture is also “the sum of its destructions.”

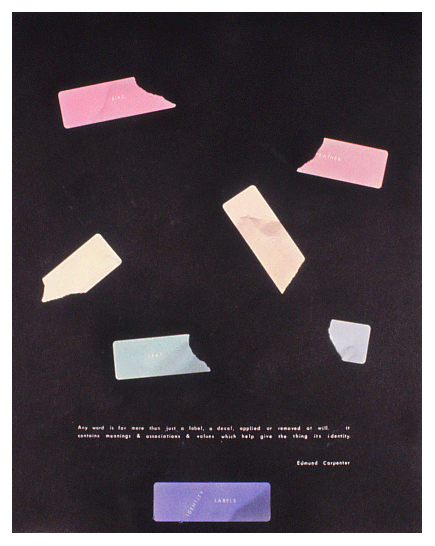

To be sure, some of the messages on these blackboards aren’t part of the public domain. Works depicting the painter’s palm prints, Florida’s palm trees, a family cat named Mau and a host of other autobiographical references are often playfully punctuated with decals (an apple for the teacher, for instance) and trompe I’oeil stencils that seem taped onto the faux-erased surface. This private iconography suggests that personal memory is also ephemeral and mutating.

Realism has always involved the creation of reasonable facsimiles. In certain trompe I’oeil instances, the facsimiles are more than reasonable. They appear to be the real thing, and so we look again. In this game of “trick the eye,” artist and onlooker are like two chessmasters, each trying to see one move ahead of their opponent. The painter must double-check every detail and hone his skills in an effort to create a seamless illusion; viewers examine the image ever more carefully to find the telltale clue that unmasks the hidden truth. It’s a difficult challenge; barring the few forgers, who have managed to avoid prison, John O’Connor is the best contemporary “counterfeiter” in the business.

THE TRUTH OF ILLUSION by Richard Vine

Richard Vine, the current managing editor of Art in America, has served as editor-in-chief of the Chicago Review and of Dialogue: An Art Journal. His articles on art, literature, and intellectual history have appeared in numerous journals, including Salmagundi, Modern Poetry Studies, and New Criterion.

John A. O’Connor is engaged in one of the oldest–and arguably one of the strangest–endeavors in the history of Western art. The impulse toward pure illusionism, the desire to fool the eye and mind of the viewer, was a major component of Greek naturalism. This shift from symbolic to lifelike representation is commemorated in the 5th-century B.C. legends of Zeuxis, who painted grapes so realistic that birds tried to peck them, and his rival Parrhasios, who tricked Zeuxis into trying to draw aside a painted curtain in order to see another “work” behind it.

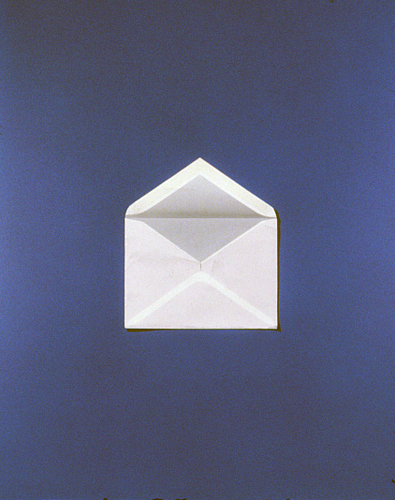

Plato, the godfather of all conservatives, deplored these confusions as a dangerous distraction from reality and truth. Ever after, nonetheless, certain artists have striven to enhance illusionism not merely for the fun of the trick (an element not to be denied) but also for the sake of a greater philosophical point. The means were dynamism, architectural framing (often extended or faked), cartellino (a object), imagistic windows and vistas, etc.–but the end effect was generally one (or more) of three. In rough terms, religious artists sought to confirm the wonder of God’s creation (the multiplicity of His creation, the perfection of His cosmic design); secular artists to celebrate the fleeting glory, the poignancy, of earthly life; and empirical, post-Enlightenment artists to point out the degree to which any model of concrete reality is a mental construct, subject to deception, preconditioning, and error.

O’Connor’s works–particularly the “blackboard” paintings, in which the invocation of a lesson is most direct–would seem to be firmly entrenched in the postmodern questioning of discourse, both visual and verbal. Clearly this is how the artist, a veteran professor, speaks of the project. Calling his method “conceptual realism,” he stresses that the teaching slate’s multiple erasures and emendations trace a history of infinite approximation, of constantly altered “certainty.” The chalkboard palimpsest refutes fixed reality, or at least any hope of an unshakable human grasp of its essence. The half obliterated letters of America (1998), reflecting a sensibility largely formed in the Vietnam War era, invite us to ask what is myth and what substance, what is transient and what permanent, in the country they name. Indeed, the link between naming and conjuration is strong throughout the oeuvre: from the insistence upon an object that is not in fact there–in works like White Slate #1 (1976), Page from a Book of Ours (1976), and Brown Bagging It (I 978)–to the suggestion of the power (and fallibility) of signs: Chinese characters in Erasing History (1989), words and letters in The Play’s the Thing (1988), numbers in The Definitive Journey (1999), and even diagrams in Johns’ Theory (2002).

Such is O’Connor’s announced stratagem. But an outside observer might well ask if there is not an implicit agenda in his work as well–one perhaps beyond conscious intent. Trompe l’oeil illusionism creates for the viewer a phantom reality, a second existence. Once, in the age of faith, this alluded, in part, to a realm of spirit behind the material. Today, in an era that no longer subscribes to transcendence, it seems to imply a love of physical reality so intense that the world must not only be made present but made present a second time–as though the artist were saying, in a protest against the loss of immortality, that one life, one encounter with earthly things, is not enough. Perhaps this is a desire O’Connor shares with the advocates of high-tech illusionism, too. What is the ultimate wish behind high-definition TV, computer assisted video effects, and virtual reality except to have this world, and have it more abundantly?

New York City, NY – April 2003

JOHN O’CONNOR: HOW YOU SEE IT, HOW YOU DON’T

by Peter Frank

Peter Frank is editor of Visions art quarterly and art critic for the LA. Weekly. In New York he served as art critic for The Village Voice and The SoHo Weekly News. Frank has also organized numerous theme and survey exhibitions for such prestigious institutions and organizations as Independent Curators Inc., The Alternative Museum, and Artists’ Space in New York; and most and most notably, “19 Artists–Emergent Americans,” the 1981 Exxon National Exhibition mounted at the Guggenheim Museum tent.

ConAlmost from the inception of his career, John O’Connor’s art has explored that fertile interstice between idea and image, that place where language sprouts, flourishes, fails, and rises again. He is not alone in plumbing these heights and scaling these depths: what he calls “conceptual realism,” where word and picture, concept and concretion mesh and metamorphose one into another, is a durable tendency in American art. But O’Connor has embraced it with a thoroughgoing passion–as well as a quick intellect and slippery wit.

Indeed, from a certain angle–one the art-historically-minded O’Connor would encourage–O’Connor’s work is summative, recapitulating various modes and aspects of conceptual realism and making them playoff one another. The trompe-l’oeil still lifes painted by late-19’” century American artists such as Harnett, Peto, and Haberle brim with the same kind of mundane but dense information, and deliver that information with the same optical trickery, as fills O’Connor’s deceptively lucid panels. The word games, image games, word-image games, and other meta-rebuses that moved from Victorian parlors to the art of the surrealists’ American inheritors, from Cornell to Comix, recur, in spades, throughout O’Connor’s oeuvre. The anti minimal, pro-regional hi-jinx of Funk art–a kind of thinking hick’s Pop–encouraged the conflation of language and image, thought and picture, medium and message.

O’Connor was schooled in the epicenter of Funk, pretty much at the moment of it’s apex, by William T. Wiley, one of its most prominent, and most extravagant, exemplars. While studying in the Sacramento area, O’Connor also benefited from the more demure, but no less heady and startling, teaching of Wayne Thiebaud, whose take on the “common image” proposed a heightened realism that worked like, but didn’t look like, both the Pop Art from back east and the trompe-l’oeil stuff of old.

Thiebaud, and in a different way Wiley, also provided O’Connor a healthy regard for studio pedagogy, encouraging him to become a teacher as well as artist and, indeed, to regard his teaching as part of his art and vice versa. Lightly but firmly didactic in their visual diction (and/or, if you would, their verbal appearance), O’Connor’s pictorial notations constantly show us how to view a pictorial notation as well as how to make one. Like an opera singer who has carefully cultivated a dramatic stage presence as well as a golden voice, and who has done so in part to be able to pass on such crucial ambidexterity as part of his or her legacy, O’Connor trains us by showing us by example–example that has not been dumbed down, but cleaned up. He entices us into his intellections not by making them less elusive (or for that matter allusive), but by making their elusions (and certainly their allusions) more inviting. If Americans can learn to eat spicy food, they can learn to “read” art.

The importance of pedagogy in O’Connor’s artistic personality–in his art as much as in his professional standing–has manifested with a kind of ecstatic clarity in his blackboard paintings. After all, as he observes, “I have been surrounded by blackboards for most of my life.” Rather than run from this recurring constant, O’Connor has made it a leitmotif, and explored it in depth–looking behind the blackboard’s obdurate surface not (just) to its associative resonance, but to its inherent visual-verbal depth and the versatility of its physical as well as social context. It is a context that allows graffiti, imagery, signage, informal notation, and pure painting to co-exists. Blackboards, he writes, “are the environment of palimpsests, ghosts of gestures, the residue of images and words linking thoughts and concepts of visual entities and written language.”

O’Connor is not alone in musing on the blackboard as physical presence and as epistemological field; artists as diverse as Arakawa and Vernon Fisher have been drawn (as it were) to the same motif for many of the same reasons. But O’Connor’s blackboard works assume a reflexive intensity not found in the art of the narrative-driven Fisher or the semiotically engaged Arakawa. In their work, as in the work of other artists (again, mostly American) who have created photo-realist chalkboard-paintings, the blackboard is a supportive construct for related concepts; for O’Connor, the blackboard is the icon–or, more accurately, the iconostasis, the defining framework for iconic presentation and discussion. The blackboard is O’Connor’s page–perhaps his book.

If O’Connor’s earlier work, before 1985, is not “framed” by the blackboard motif, it is similarly powered by the painter’s sly and technically assured exploitation of what is apparently a native gift for exactitude and concomitant disdain for the merely illustrative. O’Connor’s art has always been full of tricks, but he is one of those magicians who delights in instructing his audience in the slight-of-hand, because he knows that if the audience knows how the picture works, they’ll approach with greater confidence and broader mind what the picture says. A little knowledge may be a dangerous thing, but John O’Connor, the punning painting pedagogue, knows that a little knowledge leads to a little bit more.

Los Angeles, CA – April 2003

ILLUSION, IMAGINED REALITY by August L. Freundlich

Dr. August L. Freundlich was President of the Richard Florsheim Art Fund and also served as Dean of the College of Fine Arts at both Syracuse University and the University of South Florida.

Illusion, imagined reality, these are the substance of John O’Connor’s painting. The paintings belie the fact that his other persona–that of teacher and administrator–deals in the everyday real. That is the everyday reality faced in the university and the studio. Throughout his career, John has been widely engaged in such topics as artist’s issues in law, evaluation of college art programs, health hazards facing the artist and the censorship of art works. In the thirty-four years of his career in Florida, he has sought to establish the artist’s historical contributions to the formation of public policy by founding the Center for the Arts and Public Policy at the University of Florida and serving as director of the Florida Higher Education Arts Network. In teaching Florida’s students, he has made them aware by example of the commitments an artist must make not only to one’s art, but also to the society of this time and place.

O’Connor’s intellectual approach in his art is paralleled by his spoken and written word. Both have been accepted nationally and internationally. In recent years his blackboard series is not only a reflection of his teaching milieu, they also speak of the illusion of real experience–the transitory experience of the chalk-mark on the blackboard being erased after a short existence in time. The challenges of the painter and the professor are the same thing–expressed here on different platforms.

Sacket’s Harbor, NY

June 2003

REAL ILLUSIONS by John Grande

John Grande is the author of numerous articles that have appeared in Artforum, Sculpture, Art Papers, Canadian Forum, Vie des Arts, British Journal of Photography, On Paper, Vice Versa and Canadian Art. His most recent books include Balance: Art and Nature (1994) and Intertwining: Landscape, Technology, Issues, Artists (1998), both published by Black Rose Books, Montreal.

40″ x 30″

John O’Connor’s paintings are neither a window on the world nor are they abstract in the purist sense. The pictorial language of representation, the iconic language of abstraction, even the act of painting itself are all challenged in O’Connor’s work–not as process, but in terms of how we conceive of representation in our mind’s eye. Formal and structural precepts (the role and function of the art object) are usually defined as effects that involve a process–although they are, in fact, more often end results that have their beginnings in our cultural coding, our social precepts about the role of art.

Just as avant gardism has become a self-perpetuating social convention, much like a snake that eats its own tail only to see it grow back again, so the act of painterly representation has become histology of the meanings it rejects in circumscribing its own visual definitions. O’Connor’s “Real Illusions” move in the other direction. The imagery is temporal and trace-like–a distant echo of some pre-cognitive state of mind. The visual process is conceived as a kind of alliteration. O’Connor seems to suggest our beingness, or soul, is out there and not within us at all. Reality is elusive. Reams of material have been written on the conscious act of painting, yet no one has ever been able to prove where consciousness really exists. O’Connor’s paintings are ahistorical in the sense that no image can exist as an entity if the culture that brought it into being does not have a holistic conception of its place in the universe. O’Connor’s art is anti-metaphor, a surreal extravaganza of colliding visual anomalies. This is visual reportage in a world of virtual and visual excess.

The diverse elements painted into John O’Connor’s airbrushed acrylic paintings often resemble collage. At other times, the trompe I’ceil effects imitate object appropriations. These visual devices cause us to question the way objects and signs are used as metaphors for a reality that devalues the act of painting, rendering it merely on approximate metaphor for representation in whatever form it takes.

The experiential monoreality of today’s urban environment includes a forest of signs and symbols as confusing as the myriad of visual tricks and devices brought together in O’Connor’s paintings. The various manifestations of image culture that exist as physical entities in today’s real environments are no different in their conception than J. M. W. Turner or John Constable’s romantic nineteenth-century landscape paintings. Images and signs reaffirm humanity’s dominion over a holistic concept of nature and deny any direct connection between the two. This is a mindset that O’Connor’s unusual brand of art challenges. By juxtaposing image fragments, as they might be used in advertising, product packaging, or street signs, he reverses the effect. Instead of looking into these works, we read them as collective representations and are made aware of how chaotic image metaphors have become. The mimetic language of painting often relies on our reading of various abstract, representational, or conceptual elements. Few artists address the dilemma of illusionistic representation as a stereotype–where imagery serves to reaffirm the ingrained historical and cultural assumptions inherent to representation–as O’Connor does.

In 2 RD for the Muse (1988), what looks like a torn fragment of a Diebenkorn-esque landscape affixed to a blackboard background is, in fact, a painterly fabrication incorporated into the overall composition. The formulation of the piece is pure Pop Art, but the configuration is on informational mirror of O’Connor’s reflections on object appropriation in Pop Art. The artwork becomes a refractive planar surface prism of representation–where the objects, symbols, and abstract and figurative stereotypes are entirely self-construed. O’Connor’s paintings simulate these effects, questioning the dichotomies lying beneath any discourse on art and objecthood. In Mozart (1989), gestural arcs, musical bar lines, and stenciled letters further the sense that representation cannot, ultimately, be measured or quantified. O’Connor fills the Blackboard Series with humorous sleights of the eye. As such, any process of representation is seen to hinge its meaning on a visual language that embodies a sense of reality through the act of representation. The pointed image–be it figurative, gestural abstraction, or comprised of image fragments–seems no different in its cultural relativism from any mass produced object or symbol per se. Blackboard Jungle II (1986) achieves this effect by painting a realistic-looking piece of red chalk and yellow paper onto an ethereal background of glyphic-and-linear painted fragments that appear to have been partially erased. Using the blackboard as a metaphor for the act of pointing, O’Connor subverts the Pop Art paradigm of commercial object and image appropriation. Here is a “real” object–the blackboard as cultural artifact–that is merely a representation of itself, onto which diagrammatic, graphic, mathematical, notational words and symbols are painted. The imagery is ambiguous and suggests a cyclical, temporal illusion that parallels the way we conceive of imagery.

O’Connor reverses the order of representation in The Idiot Marks of Man’s Passing (1973) by presenting a sublime, romantic landscape in an octagonal-shaped format. At the core of this realistic scene appears a black, abstract circle. On closer inspection, the circle is found to be an aluminum mirror surrounded by fake fur in which the viewer’s image is reflected.

Iconic Pop Art elements are sometimes incorporated to contrast the temporal imagery (analogous to the thought process) that O’Connor presents. The Plays the Thing (1988), for instance, has “BLACK RUBBER BALL” scribbled into the background alongside painted imagery of mathematical notations, a red star, and a tiny card that casts a tiny pointed shadow. The stenciled lettering along two borders of the piece includes the artist’s own name. It is an autodidactic, tongue-in-cheek aside to Jasper Johns’ and Jim Dine’s deification of the object as symbolic metaphor. John O’Connor’s paintings defy categorical definitions by building visual maps in the no-man’s-land of the picture plane. Representation is unmasked and a behemoth of visual and object metaphors are unleashed. The staid language of product and object recreation that was Pop Art is revealed for what it was–an idiosyncratic embrace of materialism.

Pop Art allusions are evident in the trite white and pink silhouettes of a cat in Mau (1986). In on earlier work, titled Object Dart (1977), O’Connor avoided the target by drawing the object that flies through space to get there (a dart) in subtle ink tones at the center of one of his paper drawings. The paper creases provide a neutral background for the piece and the word object stenciled above it furthers the meditative aspect present in so many of his works from the late 1970s. The leaping tiger, the black star on a yellow square, and the calligraphic characters in A Clean Slate (1986) suggest some deeper illusionary dream state.

O’Connor’s art is a fulcrum of image fragments that challenges the materialistic myth that gave birth to object metaphors. In a paradoxical way, his art implies that representation itself is a fleeting, illusory state of mind. The graphs, graphics, glyphs, cryptogrophical notational markings, and scripted-stenciled motifs we see in these works are visual and relativistic incantations that challenge the social and cultural stereotypes of modern art history’s orthodoxies. His paintings suggest that representation of any kind involves a path of comprehension that leads one directly bock to one’s own historic and contemporary cultural coding, Rife with visual and iconic information, his art manufactures illusionary effects with an aesthetic predilection that is as conceptual as Duchamp’s readymades. Likewise, O’Connor puts together an array of alliterative visual motifs and in so doing alludes to the real dilemma of precognition with which the contemporary mind must deal. As he states: “Everything in these works is invented. I don’t paint from objects. I point from my mind.”

JOHN O’CONNOR’s 2005 RETROSPECTIVE by William Zimmer

The late William Zimmer, an art critic for the New York Times, New York City, wrote this review in 2005.

More than most artists John O’Connor is comfortable with contradiction. It’s the dynamic of his career. Some of his major paintings are exemplary specimens of trompe l’oeil that required the discipline and attentiveness of a monk copying a manuscript. Narrowness is far from all, however. For example, as a teacher he introduced the first courses in performance art in an American college.

He recently had a full retrospective of his career at two venues in Gainesville, Florida. They brought out major shifts but the road he was on was far from bumpy. There’s a logic to O’Connor’s moves, much of it based on the simple facts of his life. Early paintings influenced by the renown Bay Area Figurative Movement, whose major artists he knew, including Richard Diebenkorn and Paul Wonner, vividly portray a fine domestic. Paintings feature his wife and young son and also chronicle the rock vibrant music scene that helped make San Francisco a radical culture capital in the 1960s.

But O’Connor has never been one to slavishly follow a major style, and he found it hard to resist the influence of William T. Wiley who was teaching at the University of California at Davis with O’Connor. It is perhaps due to Wiley and his sense of the absurd that has been likened to that of a Zen master. O’Connor’s keen observation and that skill came to the fore in a kind of absurd way in the trompe l’oeil paintings that followed. The new focus of O’Connor’s paintings became the sky. To be able to imitate the stuff of life in a painting, like 19th century painters such as Harnett and Peto did, is a kind of feat. In their manner, O’Connor could make it look like a real piece of cellophane tape was holding down the objects, admission tickets and crumpled receipts from daily life which he copied, making them look astonishingly real.

The next enthusiasm is widely considered to have engendered O’Connor’s most important work, the Blackboards, which began in the 1980s. In a way they are directly related to the trompe l’oeil paintings; both feature flat surfaces covered with information, momentous or not. But the power of trompe l’oeil is that it presents its ephemera as lasting for eternity, while blackboards are erased leaving palimpsests. Such traces of time keep the paintings fluid. They can hold any kind of content even the absurd kind, as they implicitly state that they are records of the transient nature of thought and ideas.

O’Connor rightly sees Jasper Johns as the immediate source of the Blackboards. Early on, Johns postulated a blackboard when he created his mutable numbers and letters. He has always favored gray, which hints at gravity and deep thought, even though what may appear is finally incomprehensible Dada. O’Connor also makes great use of the stencil, which is practically a Johns trademark. Stenciled writing signals something profound and lasting. Whatever O’Connor’s myriad influences, he openly acknowledges them, but he also digests them, along with what has been imparted over the years, to create an art that is fully his own.

The most recent paintings have ascended into grandness. First of all they are very large and polyptychs have appeared. If rock and roll was the impulse for some of the 60s paintings, Opera is now. Mozart’s “Idomeneo” was summoned up in a large black painting, and in 2003 O’Connor paid lavish homage to Strauss’s “Arabella.” Butterflies have gotten their majestic due on a large canvas replete with them. Although they might resemble pinned-down specimens, the butterflies might be a symbol of O’Connor’s mutableness, and above all, freedom.