My Life / My Art

Many things influence an artist’s work. Concepts are forged from impressions, imagination, relationships, education, meditation, dreams, travel, language, other cultures, and various experiences of realities.

From about the age of three, I had wanted to be an architect. When I began the first of my many college experiences at Sacramento City College in January 1957, I primarily studied architectural design, mathematics, and Spanish. After two years there, I decided I had no idea what I wanted to do, so, in January 1959, I quit and moved to San Francisco and took a job with the State Compensation Insurance Fund while I continued to paint in the evenings and on weekends. That experience made me realize that I didn’t know very much about art after all. I had a revelation: if I could admit that there was much left to learn about art and life, I probably ought to go back to college, become a serious student, and really learn about it. So, in summer 1959, I attended Sacramento State College’s Lake Tahoe branch campus (now California State University-Sacramento) for an intense six weeks of painting and drawing with artist Fred Schmid who advised me to continue my study in Mexico. In the fall of 1959, I enrolled at Mexico City College (now University of the Americas) and began a serious study of painting and art history. I sat in on a graduate seminar taught by the renowned art historian John Goldberg, and I visited every Mexican Mural Movement site I could find. However, by the end of my second quarter there, my mother was terminally ill, and I returned to Sacramento in January 1960. From then until summer when I again enrolled at California State University-Sacramento (Lake Tahoe branch) and took additional classes with Fred Schmid, I painted on my own in a converted garage-studio at my home.

Bay Area Figurative

From 1958 to 1968, I worked in a manner known as Bay Area Figurative. I was greatly influenced by this vibrant, new style that was just beginning to emerge in northern California in the late 1950s. David Park, Elmer Bischoff, and Richard Diebenkorn are credited as the founders of this movement, and I readily acknowledge their influence on my early works.

However, it was studying with artists Greg Kondos and Wayne Thiebaud at Sacramento City College, and William Theo Brown, Roland Petersen, Wayne Thiebaud, and William T. Wiley at the University of California-Davis, and James Weeks at the San Francisco Art Institute, and my exposure to the work of Paul Wonner, that created the context for my early work to develop. Like many of these artists, I was aware of our extraordinary surroundings: the grand California land and seascape. However, during this time, I also explored a wide variety of subject matter that included the human figure and still lifes.

My art works during this time are characterized by vivid color, and a sensual, painterly and, somewhat, expressionistic style. I was also especially interested in the effect of light on interior surfaces. Many images were derived from personal experiences and observation in the mountains of northern California or along the jagged beaches from Monterrey to Mendocino. When I moved to Santa Barbara in January 1963 to begin teaching at the University of California-Santa Barbara, images of bathers, surfers, and the softer, more accessible, southern California beach scenes became a major interest. I also did numerous paintings of my wife Mallory and son Chris and painted some of the rock music stars of the 1960s.

Reality and Illusion

In 1968, I began to explore new ways of working. I had moved to Ohio in 1965 to teach at Ohio University, and my new environment was a shock to me. The landscape was completely different, the light softer, the air much more humid, and the sky was frequently filled with lightening of an intensity that I had never encountered. Although I continued to work in the Bay Area Figurative style after arriving in Ohio, I found it harder and harder to do so. As I responded to my new environment, I began to experiment with new ideas.

In 1969, I moved to Florida to take a teaching position at the University of Florida in Gainesville. Although it was déjà vu all over again, I had less difficulty continuing with my work because, since I was painting from my imagination, it was less environment-dependent than ever before.

I called the paintings from 1968 to 1986 Conceptual Realism. They are the record of a journey to explore the mystery of illusion and reality. My goal was to provoke thought about how we create our reality. Humor, paradox, deception, and riddle are aspects of this working/process. The result is conceptual realism—not new realism or photo realism. Everything in these paintings is invented. I didn’t paint from objects, I painted from my mind. I was interested in things the mind thinks it knows, things seen but not apprehended, things perceived but not truly experienced. By 1986, this particular period in my art practice had completely evolved into the Blackboard Series.

Blackboards

Since 1985, the Blackboard Series has been the predominant form of my art. It grew out of work produced in the early 1970s, but the impulse that led to the blackboards was largely undeveloped and not recognized by me. Art has a peculiar way of telling an artist something that he may not understand for many years.

The blackboards images, obviously originated from my classroom experience where I had been surrounded by them for most of my life–first as a student, then as an artist-teacher. As early as 1963, I was interested in the idea of how natural processes could contribute to making a work of art. The blackboards are created using those kinds of processes. Erasing and moving borders become a history lesson: a history of the work itself. Wiping out and/or covering up images and messages goes far beyond the processes themselves. The procedure raises significant questions: What is covered up? Why? What is missing? Within this context, I have become interested again in the concept of the “history painting” in the tradition of such eighteenth century artists as Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley. In a1989 painting titled Erasing History, I explored the practice of manipulating “historical facts” as a form of propaganda; more recently, in paintings such as America and The New Ivory Tower, I have focused on the manipulation of words and symbols as “historical documents” used to sway public opinion and to reinforce popular mythology. In addition, the didactic quality of the blackboards allows them to be utilized to fulfill their real function: to inform, to explain, and to teach. It is interesting to note that one of the most influential educational innovations in America in the1870s was the introduction of drawing as a required subject in public elementary education. Drawing instruction was justified as valuable training in visual literacy. Teachers used the classroom blackboard to illustrate the basic principals of line, shape and proportion. For my own purposes, the blackboard is the ideal conceptual vehicle because it is the medium par excellence with which to manipulate ideas and material.

A critic once said that my blackboards reminded him of “those waxy tablets with the thin vinyl sheet over the top that some folks still remember writing on as a child.” He pointed out that such a device is called a palimpsest, a magic slate on which images could be drawn and then magically erased by lifting the vinyl sheet. Interestingly, the palimpsest was one of Sigmund Freud’s favorite metaphors for the unconscious. Encountering my blackboard paintings, the viewer is invited to enter an environment of palimpsests: ghosts of gestures, the residue of images and words linking thoughts and concepts of visual entities and written language. They are the tracings of a life’s journey. Partially erased, but not forgotten, my blackboards provide a dark window into the modern psyche. Like us, they may be but fleeting illusions, or they may establish our own reality against eternity

It is tempting to suggest that both my Conceptual Realist paintings and their transformation into the Blackboard Series owe their form to nineteenth century trompe l’oeil painting and are merely an extension of that genre. However, that would be erroneous. One of the concepts that I have steadfastly developed is that of going beyond traditional illusionism. Typical trompe l’oeil painting, no matter how initially deceptive, inevitably breaks down under close scrutiny. In my blackboard paintings, I invite the viewer to question the nature of reality itself. Consequently, I have developed concepts and techniques to create realities that are the vehicle for such transcendence. All of my blackboard paintings are done in acrylic on board or Sintra–there is no collage. While I enthusiastically admire the trompe l’oeil masters of the past, my own work has evolved primarily as a result of twentieth century influences found in the works of William T. Wiley, Jasper Johns, and particularly, Marcel Duchamp.

Folding Screens

My notes on, and research into Oriental folding screens, dates back to the mid 1970s. Again, it was an inspiration that I did not even begin to start to fulfill until 1984. And, although I painted the first of the “Folding Screens” in 1984, and, even though I continued to research, makes notes for, and develop ideas about them, I did not fully return to this genre until 2005 with the painting Butterfly. My folding screens, while ostensibly decorative, encompass a space for private reflection–there’s more to them than meets the eye. Like the Zen koan, they also pose a riddle, a paradox, and an unanswerable question: illusion or reality?

The folding screens are a significant current interest. However, I am continuing to work on the Blackboard Series (which has morphed into the Chalkboard Series that blackboards, whiteboards and greenboards–the last two that have replaced most blackboards in the classroom). And I am producing many examples of both forms of illusion and reality as “virtual” works of art. Using an i-Mac, I am able to generate numerous “scripts” for future works–some of which will be tangibly realized and others that will be available as commissioned works.

So, although my paintings have gone through several incarnations, they inevitably ask the same questions? And, since the questions can’t be answered, they continue to motivate me, at seventy-five years old, to continue to explore what I initially set forth: an art forged from impressions, imagination, relationships, education, meditation, dreams, travel, language, other cultures, and various experiences of realities.

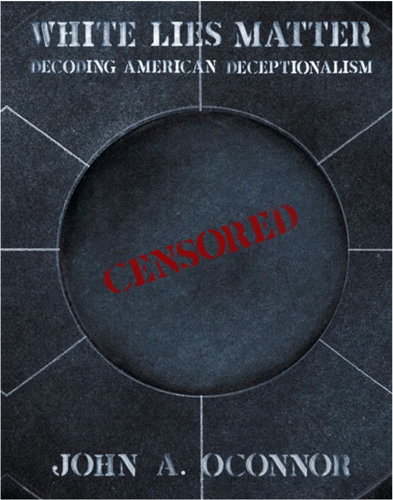

Slates

Beginning in the early 1960s, John A. O’Connor, “the punning, painting, pedagogue”

began a series of paintings, drawings, and works on paper that included satire, social criticism, and anti-mainstream commentary on a variety of issues. Taking his lead from artists like Hieronomus Bosch (The Garden of Earthly Delights, The Last Judgment, and The Haywein Triptych) William Hogarth (A Harlot’s Progress, A Rake’s Progress) and Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (Los Disparates [The follies, The Proverbs, and/or The Dreams]; Los Disastres de la Guerra; and, especially The Black Paintings), O’Connor initiated a second side to his better-known work (Bay Area Figurative). Including word-plays made with stencils, irreverent dialog, and a take on the more serious works by Jasper Johns, O’Connor started to develop a group of themes and images that would recur throughout his career and subsequently lead to the current series, White Lies Matter.

This series of “fake slates” explores many popular misconceptions that we all share about what is really going on in our lives. A symbol of the only Irish pub on communist soil at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba “where it don’t gitmo better than this,” and Bill Clinton’s “little blue dress” episode looks downright insignificant when compared to JFK’s exploits, and the real story behind Obama’s “red line in Syria,” White Lies Matter exposes the cover ups, lies, and cynicism of 21st century America.

John A. O’Connor

Micanopy, FL

November 2017